For those who follow the news a little, two interesting articles appeared last week that touched on the metal demand of our new economy. Our dependence on China, among others, as a supplier of critical metals is increasingly on the agenda. There is also the problem of the availability of these critical metals. This raises the question: what are we going to do?

Problem 1: Dependence

Last week, the European Commission published the updated critical raw materials list – an overview of metals that are critical to the functioning of the European economy. The Financial Times published a much-discussed article about what geopolitical dependence on China means for Europe’s sustainability ambitions. The Dutch Broadcasting Foundation NOS explained the conclusions (in Dutch) to the Dutch audience.

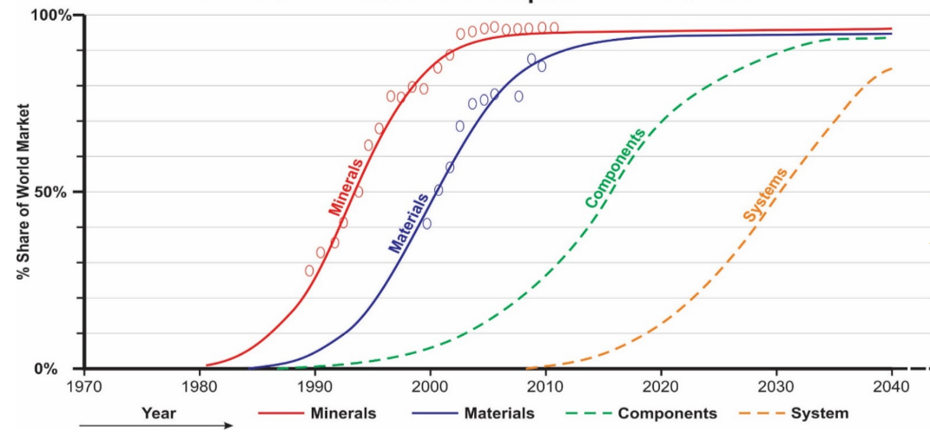

The challenge is that the metals required for the production of our sustainable technologies – including solar panels, wind turbines and electric cars – are almost all turned into the final product in China. This isn’t because we can’t develop the industry in Europe, but rather because in recent decades, China has taken more and more steps in its own production chain – from refining to the production of components, and more recently, assembly.

The growth of the Chinese market share in mining, refining, production and assembly (Van den Boogert, 2014)

The consequence is pretty simple: we can’t buy the solar panels, wind turbines and electric cars we so desire without Chinese producers in the supply chain. Just like it is for our washing machines, microwaves and consumer electronics, by the way.

A brief parallel to the Coronavirus pandemic: we see the same thing happening with metal components as we did with face masks before the pandemic. In recent years, China has taken over world production of face masks, making other countries dependent on Chinese production. The main difference is that the materials for mouth masks are fairly easy to purchase, which means that production can be scaled up quickly. However, the same does not apply to critical metals.

Problem 2: Availability

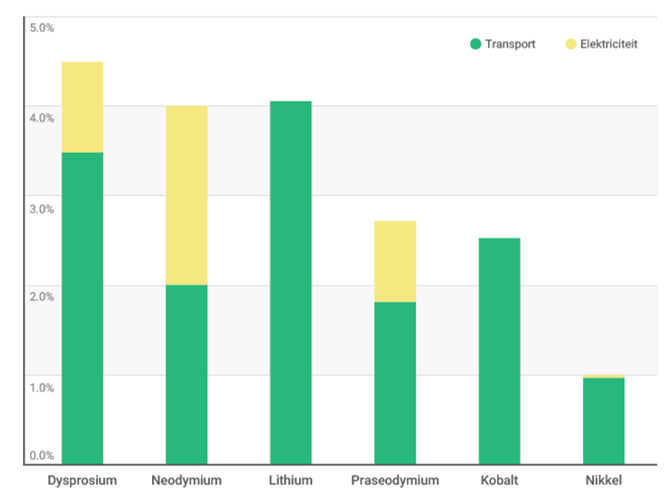

The challenge to achieving the objectives set out in our own Climate Agreement lies not only in the pace of decision making and support among citizens, but also in the availability of the necessary materials. In two studies – Metal Demand for renewable electricity generation in the Netherlands and Metal Demand for Electric Transport (Metaalvraag van Elektrisch Vervoer in Dutch, 2019) – we estimated the order of magnitude of our demand for critical metals for sustainable technologies.

When we look at current worldwide production (‘supply’) and the metals required for solar panels, wind turbines and electric cars (‘demand’), we see that Dutch demand is considerably higher than the reference share the country would be ‘entitled’ to based on global supply. You could argue that the Netherlands being at the forefront of the energy transition justifies the fact that the country uses more metal than its reference share. However, the IPCC argues that the path of the Dutch reduction – 49% by 2030 – is the global minimum needed to stay below two degrees. If the Netherlands wants to set an example for the rest of the world, we will have to take into account the metal demand associated with our choices.

The Dutch demand for several critical metals as a result of the Climate Agreement (2030), plotted against current worldwide production (2019). (Copper8, Metabolic & CML, 2019)

The need for systems thinking

In the Netherlands, we’re quick to think of innovation as a solution to a problem. Have we got a nitrogen problem? Then we innovate with the composition of animal feed. Do we have a plastic soup problem? Then we’d rather follow Boyan Slat as a leader than introduce a deposit on plastic bottles. We find it difficult to tackle the system, such as altering the intensity of our agriculture or developing a good collection system for plastic. But according to our research, technical innovations alone will have too limited an impact.

We argue in our reports that if we want to reduce our geopolitical dependence (problem #1) and physical dependence (problem #2) on critical metals, we need to think at the system level. We see the following solution paths:

- In the area of mobility, our focus will have to be on fewer vehicles. Additional advantages are fewer traffic jams, less pollution (and something with nitrogen?) and more space for green areas in the city.

- Keeping our sustainable electricity grid stable requires the right balance between energy storage and the expansion of grid capacity. We can reduce metal demand by making the right decisions here.

- For solar panels and wind turbines, we simply need enormous upscaling. The challenge lies mainly in a different design that makes recycling in the future possible.

Two problems, one path

Back to Europe. In the Action Plan, which was published together with the critical raw materials list, the European Commission indicates that, among other things, it wants to focus on:

- more high-quality recycling;

- a more resilient production chain;

- more diversity in the countries critical metals come from.

These issues have been mentioned for many years, but they have barely been put into practice. To quote investigative journalist David Abraham: “China focuses on internalizing the supply chains, Europe focuses on writing reports on how bad the situation is.”

These two challenges – geopolitical dependence and availability – therefore have the same solution path: the structural reduction of our metal demand. So it’s time we dared to acknowledge these two challenges. If we do that together, we can actually make the right choices at system level. That way, we won’t remain dependent on external influences, but determine our own future.