We have a housing shortage in the Netherlands, according to an increasing number of sources. Minister Hugo de Jonge calls it a ‘housing crisis’, in particular for young people and refugees with a temporary asylum residence permit. The word ‘crisis’ seems to be the justification for building homes that this group needs in the short term. But isn’t the creation of a stock of suitable housing something that requires a long-term perspective? And by taking this crisis approach, won’t we be building houses that are destined to stand vacant in the future?

I believe we are looking too unilaterally at the housing shortage in the Netherlands. We’re mainly looking at the construction of new buildings, and only to a limited extent at making better use of existing ones, including by splitting up larger homes. In the National Housing Programme, the word ‘split’ (splitsing in Dutch) appears seven times, compared to 481 mentions of the word ‘build’ (bouw in Dutch).

There’s already a lot of living space in the Netherlands

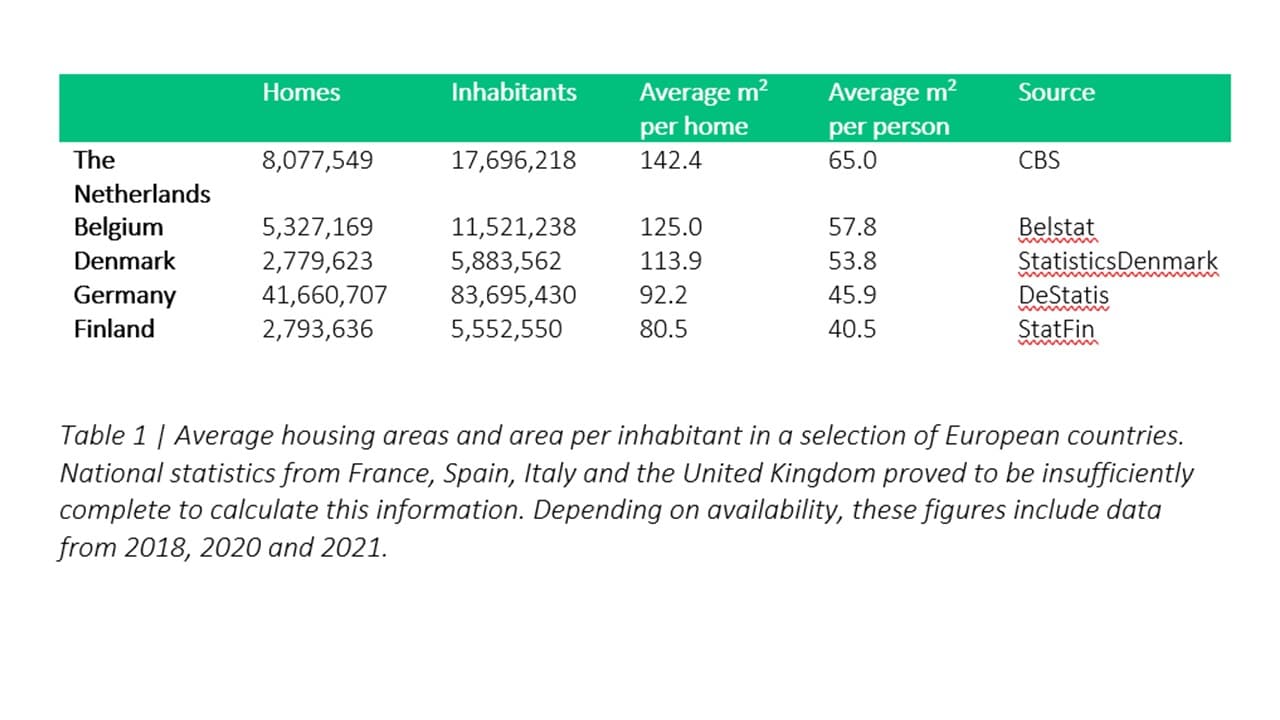

We live in big spaces in the Netherlands, with an average of more than 142 m2 per home and 65 m2 per inhabitant. It should be noted, though, that the living areas per person differ enormously, as do the associated costs. Students live in less than 10 m2 (for many hundreds of euros), while the elderly have an average of more than 100 m2 at their disposal (sometimes almost for free, because they have paid off their mortgage).

These Dutch living areas are large compared to those of other countries in North-West Europe. The countries with the biggest living space per person include Belgium (57.8 m2) and Denmark (53.8 m2), with living areas of about 10 m2 per person smaller than the Netherlands. Then come Germany (45.9 m2) and Finland (40.5 m2), with considerably smaller living areas.

The existing stock could be put to better use

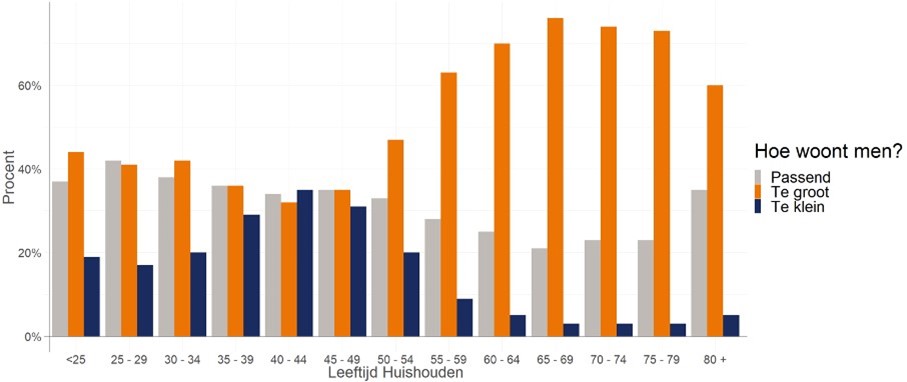

The current stock of existing homes could be used much more effectively. An analysis by Springco Urban Analytics shows that, theoretically, the existing housing could accommodate an additional 3 million people. They arrived at this conclusion by looking at the average living space per household size, compared to the space in which those households currently live. At the moment, those using the most space are empty nesters – parents whose children have left home – and seniors. Indeed, municipalities say the biggest cause of the housing crisis is the inadequate flow-through of this group to smaller housing.

In my own surroundings, I hear from many people in this group that they are looking for a smaller home, but simply cannot find one. If there were a larger supply of apartments available for this group, many young people (and refugees) could move into the single-family homes that would become available when they moved.

Figure labels:

- Percent

- Age of the householders

- How much space do they have? Suitable / Too big / Too small

Figure 1 | Number of people living in areas that are suitable, too big and too small (by household age) – source: EDM, BAG 2020

Current production: mostly single-family homes

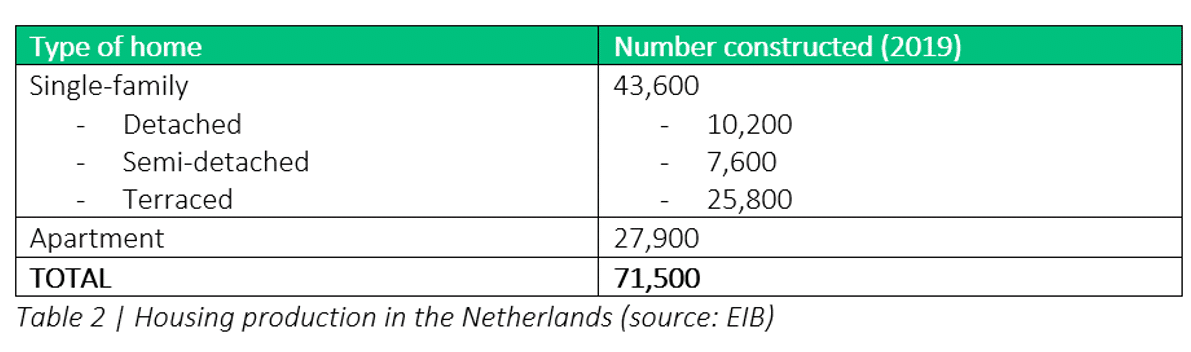

At the same time, we are still building more single-family homes than apartments in the Netherlands, according to figures from the EIB (for 2019). In 2019, we built more than 43,000 single-family homes, compared to just under 28,000 apartments. In addition, as Follow the Money recently showed, the political lobby is focused on building in rural areas, where developers have major commercial interests. And those outlying areas are particularly suitable for… single-family homes.

The construction of single-family homes follows the current demand from home seekers. We don’t dare to focus on constructing apartments (especially for seniors), which would get the flow going and provide everyone a suitable living environment. Building all those new homes – especially when construction is scaled up – leads to considerable use of materials, and it has a major environmental impact. And on top of that comes the energy consumption from heating all those extra square meters.

The current way of building creates dilemmas for the sustainability objectives related to climate and the circular economy. Based on 1200-1300 kg of material per m2 gross floor area (GFA), which currently mainly consists of concrete, steel and brick, Metabolic estimates that annual new construction (in 2019) would lead to around €362 million in environmental costs (ECO). These are costs that must be incurred to restore the climate, nature and other ecosystems as a result of the negative impact.

Solution: move our focus from ‘square meters’ to ‘front doors’

In order to work effectively to solve the housing crisis, it’s therefore important that we talk less about building houses and more about solving the housing shortage. This means we’ll look for solutions that are much broader than building new homes based on the current demand from home seekers.

Based on the above analysis, I propose three possible solutions:

- Better use of existing homes, whereby we’ll work actively on tax schemes that encourage cohabitation and promote flow-through (see #3). This would reduce the number of square meters required per inhabitant.

- More effective use of existing living space, whereby we divide larger homes to create more front doors (and therefore more homes) within the current living space.

- Building homes based on the total stock, taking into account what the additional needs are across the entire housing stock. With this, we could build more apartments, so that empty nesters could move, releasing single-family homes for young families.

In summary, instead of thinking in terms of ‘square meters,’ I advocate for thinking in terms of ‘front doors.’ After all, if we created more front doors within the existing number of square meters, we would need to build less and use less material, and we would avoid the additional energy demand. Not only would this mean removing production pressure from the construction sector and politicians, we would also be creating a building stock to fit our future needs.